It was a never a secret. For decades, doctors and public health officials knew that racial and ethnic minorities experienced worse health outcomes than white Americans in nearly every category of disease and ailment—including heart disease, diabetes, HIV, and infant mortality. Until 20 years ago, however, they were split on the impact that health care quality had on those disparities.

In the 1990s, research increasingly showed that “if two people arrived in the emergency room, and all things were equal except for the color of their skin, there were differences in the quality of care that patients received,” says Joseph Betancourt, MPH ’98, senior vice president, equity and community health, at Massachusetts General Hospital. But some argued race had nothing to do with it, except as a stand-in for other factors, such as poverty or education, that disproportionately affect minorities. Finally, the quasi-governmental Institute of Medicine commissioned a blue-ribbon committee of doctors, nurses, and health officials to settle the matter, specifically examining why those disparities existed, and what could be done to address them.

Among those who helped push for the report was the late Jack Geiger, SM ’60, professor emeritus at City College of New York, who would go on to write one of its chapters. He also recruited David Williams—now Florence Sprague Norman and Laura Smart Norman Professor of Public Health and Chair, Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, at the Harvard Chan School, then at the University of Michigan—to serve on the committee. In the early 1990s, Williams had developed the Everyday Discrimination Scale, a tool used in studying the ways race affected how people were treated on a day-to-day basis. Other Harvard Chan School faculty who contributed to the report were the late W. Michael Byrd and his wife Linda Clayton, both instructors in public health practice. Byrd served on the committee and he and Clayton co-wrote a chapter.

The committee began systematically examining the evidence, looking at more than 900 peer-reviewed papers that controlled for poverty, education, and other social determinants of health to focus specifically on the impact of race in the quality of health care, concluding in no uncertain terms that it played a role in the receipt of inferior care that could lead to poorer outcomes. “I still remember one of the early meetings of the committee: When Jack Geiger presented his review of the literature there was a hush in the room. You could have heard a pin drop,” Williams says. “The evidence was overwhelming that there was a problem.”

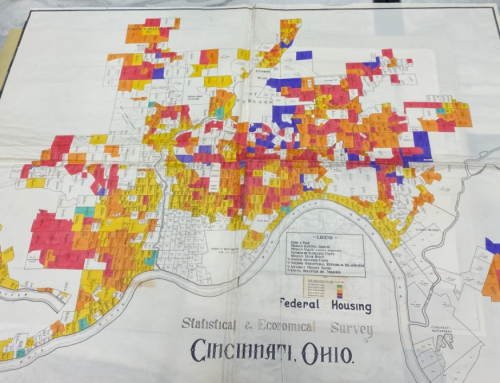

The landmark 2002 report that the committee produced, “Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care”, made the nightly news on all of the major networks on the day it appeared. It reverberated through the health care establishment, detailing unequivocally the harmful disparities minorities experienced in the health system. “The sources of these disparities are complex, are rooted in historic and contemporary inequities, and involve many participants at several levels, including health systems, their administrative and bureaucratic processes, utilization managers, health care professionals, and patients,” the report stated in its abstract. No longer could access to treatment be explained away as a function of economic circumstances.

Written by: Michael Blanding